New Orleans fears triple threat of storm surge, river, rain

Published 4:33 pm Friday, July 12, 2019

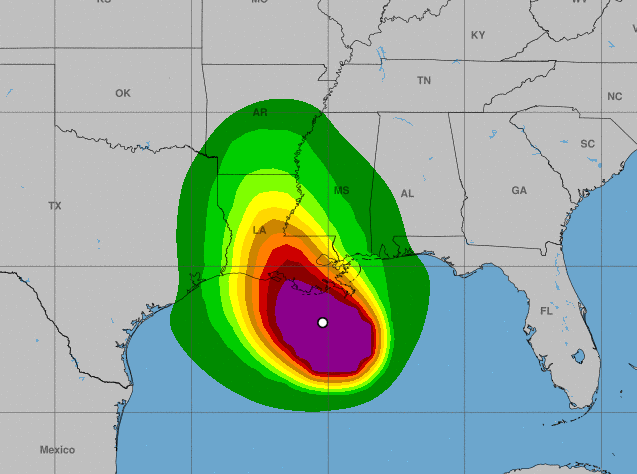

- Tropical Storm Berry is forecasted to bring a lot of rain to Louisiana and surrounding states this weekend.

By REBECCA SANTANA

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — When it comes to water, New Orleans faces three threats: the sea, the sky and the river.

Tropical storms and hurricanes send storm surges pushing up against the city’s outer defenses. That’s what happened in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina’s surge caused widespread levee failures and left 80% of the city under water.

Massive rains like those expected to accompany approaching Tropical Storm Barry have to be pumped out, taxing the city’s ancient and historically underfunded drainage system. And the Mississippi River, which drains most of the water that falls in a vast section of the United States and even parts of Canada, is held in check by tall levees . Here’s a look at the defenses that protect the New Orleans area and risks that remain:

POST-KATRINA IMPROVEMENTS

After Hurricane Katrina, billions of dollars were spent to improve the system of levees, pumps and other infrastructure that protects the city from storms coming up from the Gulf. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers worked to raise levees several feet, install new stronger floodwalls at critical places and strengthen almost every section of the 130-mile perimeter that protects the greater New Orleans area. The system is built to hold out storm surge of about 30 feet where the city’s boundaries meet the swamps and lakes near the Gulf of Mexico.

The post-2005 improvements include several massive floodgates that are shut when a storm approaches. In particular, a new surge barrier and gate that closes off the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal near the Lower 9th Ward has reduced the risk of flooding in an area long viewed as the city’s Achilles’ heel.

But experts note that the system was built to protect against a 100-year level of storm surge — a surge that has a 1% chance of happening any given year. With rising seas from climate change and subsidence in Louisiana’s coast, there’s concern that simply isn’t enough.

THE RAIN

One of the key concerns with Tropical Storm Barry is the amount of rainfall it will bring — a particular problem for the low-lying city. Rainwater is pumped out through a century-old system of canals, drainage pipes and pumps — all suffering from decades of neglect laid bare during a particularly bad August 2017 deluge that dropped as much as 9 inches of rain in a three-hour period.

Since then, the city’s Sewerage and Water Board, one of the key agencies responsible for drainage, has poured tens of millions of dollars into generating power to make sure there’s enough power to keep pumps working.

And they’ve improved systems to allow operators to see in real-time how the pumps and turbines are operating. The city also has moved to clean out catch basins to make sure water flow isn’t impeded.

Ahead of Barry, officials said 118 of the city’s 120 drainage and constant-duty pumps are available. That includes major drainage pumps able to move 1,000 cubic feet of water per second.

But officials also have cautioned that the system can’t prevent all flooding. An intense rainstorm or a slow-moving hurricane that sits over the city could overpower it. They’ve also emphasized the need to do more things such as ripping up concrete, building water retention ponds and underground cisterns. All of these so-called green infrastructure projects are designed to let rainwater seep slowly back into the earth instead of pumping it out.

THE RIVER

The New Orleans area is protected from the mighty Mississippi River by levees that started going up right around the time of the city’s first settlers three centuries ago. Reinforced and strengthened over the years, they are now about 20 feet to 25 feet (6 to 7 meters) high, and have never been overtopped in the city’s modern-day history. But they have become more of a focus during the run-up to Barry because of a rare confluence of events. The river, swollen by months of rain in parts north, will be coming up against a storm surge from the Gulf that will make it difficult for river water to flow out.

In a news conference Friday, the governor said it would be the first time a hurricane made landfall in Louisiana when the Mississippi River was already at flood stage.

The river had been expected to crest at the same height as the lowest parts of the levees, raising concerns of overtopping levees or water splashing over the levees. But now officials are saying the forecasts for the river have gone down slightly.

The levees are regularly inspected for seepage or other indications that the structural integrity is compromised.