Dr. Wayne Flynt talks Harper Lee during library speaker’s series

Published 10:30 am Saturday, January 28, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

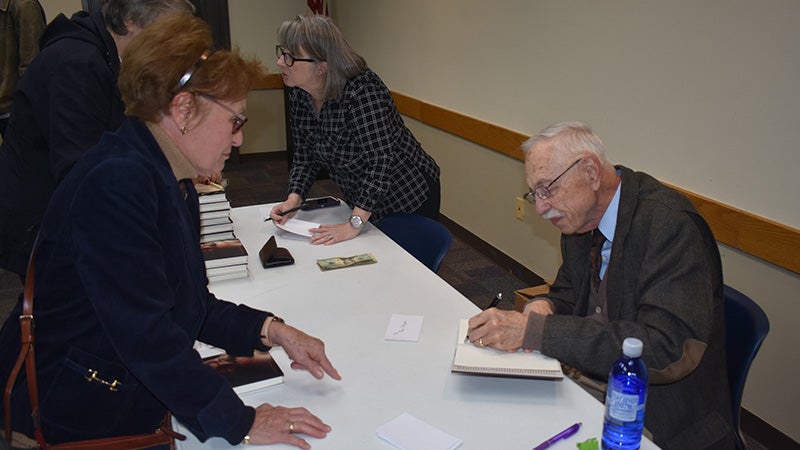

VALLEY — At Bradshaw-Chambers County Library’s Thursday speaker’s series, Dr. Wayne Flynt talked for more than an hour-and-a-half about famed Alabama author Harper Lee. It’s a subject that’s close to his heart. Flynt and his wife Dartie became good friends with her over the last nine years of Lee’s life. Dartie, a preacher’s daughter who grew up in Fairfax, befriended Lee when they were both dealing with a disability, Lee was confined to a wheelchair after suffering a stroke, and Dartie was dealing with Parkinson’s disease. The Flynts were among few people who knew the To Kill a Mockingbird author by her given name of Nelle.

Lee had two hometowns. Monroeville, Alabama was the place she was born, grew up and died. New York City was her adopted home, the place where she became famous for her bestselling book and where she was still living when disabled by a stroke in 2007. She then returned to Monroeville, where she spent the final nine years of her life.

From the time it was first published, To Kill a Mockingbird was an instant classic. It won a Pulitzer Prize for her in 1961 and was the subject of an Academy Award-winning motion picture in 1962.

That book was a hard act to follow. Lee earned fame and notoriety from it but never followed it up with another novel. She rarely granted interviews and gained a reputation as a recluse.

On Thursday, Flynt said that in reality Harper Lee was a complex person who had never let fame go to her head. She spent her final years in an assisted living facility in Monroeville. There was only around a dozen people there, hometown friends she would often laugh and cut up with.

Flynt began to see this side of Lee when he was a professor at Auburn University. He got to know her older sister, Louise Lee Connor, when they were taking part in an outreach program for Alabama’s smaller cities. He was trying to line up a program for Eufaula and knowing of Lee’s closeness to Truman Capote, asked Connor if she cold get him to come and spoke.

Not possible, she told him, “but I can get my sister.”

Having Harper Lee come and speak, Flynt said, was the sort of thing he never expected. “Sometimes you get to meet someone you never expect to meet,” he said. “That’s the way it was with me and Harper Lee. All of us on the committee were shocked. Everyone knew Harper Lee did no public speaking.”

Lee came to the event with her sister but told people “she was as scared as an owl when the sun comes up.”

She read from a manuscript and afterward signed copies of To Kill a Mockingbird for children.

“I gave her a copy I had with me. She told me she wouldn’t sign it because I wasn’t a child,” Flynt said with a laugh.

Flynt said that Harper Lee was a private person who often felt intimidated by crowds.

He asked the library crowd to think about her being reluctant to speak to a small-town group in her native Alabama. “She was the author of one of the most beloved books of the Twentieth Century, and she is nervous about speaking to a small group of people,” he said.

A few years ago when The New York Times was celebrating its 150th year in reviewing books, their readers were asked to tell them what was their favorite book from the past 150 years. Thousands of people from all over the U.S. and from many foreign counties responded, and To Kill a Mockingbird was the winner by a landslide.

People worldwide admire the wisdom and moral courage shown by small town Southern lawyer Atticus Finch in defending Tom Robinson, and they loved such passages as: “Shoot all the bluejays, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird. They don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in the corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us.”

Flynt said that Harper Lee came from a family where most of her close relatives went to Auburn. She spent two years at the University of Alabama with the ambition of following her father’s footsteps and being a lawyer. She dropped out after two years after being persuaded by childhood friend Truman Capote to come and live in New York City. “If you want to be a writer,” he told her, “you need to be in New York.”

Lee had known Capote since she was five years old. He was a neighbor of hers at the time. She was something of a tomboy and would stand up for him when the town bullies taunted him as a sissy.

Capote (1924-1984) was a native of New Orleans and was well known by the late 1950s for his novel “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

In the 1960s, Lee collaborated with him in writing “In Cold Blood,” which is now recognized as one of the all-time great true crime novels. It’s based on four members of a Kansas family who were murdered.

Lee traveled with her long-time friend to Kansas and compiled over 90 pages of notes that went into the writing the book. Capote dedicated the book to her, but Lee felt she deserved more than that.

“She wanted to be the co-author,” Flynt said.

It’s probably something she deserved.

Jealousy, along with Capote’s alcohol and drug abuse, were factors in the eventual breakup of their friendship. It bothered Capote that Lee had been awarded a Pulitzer for her first book, and he had never gotten one.

During his presentation, Dr. Flynt was floored when an African-American brother and sister in the back asked him if he was familiar with Harper Lee’s research into a murder that had happened in Alexander City in the 1970s. They told him they were the children of Robert Lewis Burns, the man who was tried for killing Rev. Willie Maxwell in June 1976.

“I have spoken about this all over the United States, but this is the first time I have ever met anyone related to Mr. Burns,” Flynt said.

The younger cousins, Jacqueline and Kenyon Heard, today live in Camp Hill. Their father is still living. He’s 82 and wanted to come with them but was ill on Thursday.

Maxwell had collected insurance money from four mysterious deaths of people he was close to. He stood to benefit from a fifth unusual death when Burns gunned him down in front of an estimated 300 people at the funeral of 16-year-old Shirley Ann Ellington, who had been found dead under the wheel of Maxwell’s car.

The funeral was held in a red-brick chapel in Alexander City. It took place on a hot summer day with many of those seated on the church pews cooling themselves with fans that had been given out by the funeral home. Maxwell was among the mourners. During the service, a woman stood and shouted at him, “You killed my sister and you are gonna pay for it!”

Maxwell, seated near the front, turned to glare at her, and Robert Lewis Burns, who was seated in front of Maxwell, turned around and fired three bullets into his body. He was dead before he hit the floor, still clutching the funeral home fan and handkerchief he’d been using the wipe sweat for his forehead.

Burns, who was a truck driver at the time, confessed to the killing. “I had to do it,” he told police. “and if I had to do it over again, I would.”

Tom Young, who was the district attorney at the time, told the jury that Burns had acted as “a one-man lynch mob.” Burns was defended by Tom Radney, one of few white attorneys who would take the case. It was an about face for him – he’d previously represented Maxwell and had gotten insurance money for him in the four previous deaths. Some people have called Radney the Atticus Finch of Tallapoosa County.

It was a show trial that attracted national attention. Harper Lee saw it as an opportunity for her to write a true crime novel. Alexander City was only 160 miles from Monroeville, and her niece owned the Horseshoe Bend Motel, where she could stay for free during her research.

Some townspeople still remember Harper Lee’s time in Alexander City for her being an independent-minded woman who was given to some smoking, drinking and the use of an occasional four-letter word. Tom Radney’s widow, Madolyn, remembered her cute wit. “She was smart,” she said. “I enjoyed just listening to her, just sitting back and listening to the conversation.”

Emotions were running high in Alexander City at the time. Lee started getting anonymous letters telling her that she was “messing with something you don’t need to be messing with” and “you will leave here if you know what’s best for you.”

Some dead cats were left hanging on people’s doors.

Harper Lee came to Alexander City thinking she could write a true crime story that was better than In Cold Blood but left thinking it was not worth the risk.

There’s an amazing story left to be told to a wide audience, and Dr. Flynt believes it may yet be done. A writer named Casey Cep has written a book entitled “Furious Hours” that gets into the Willie Maxwell story. “It ’s a much more complicated story that In Cold Blood,” Flynt said.

Flynt was friends with Opelika attorney John Denson who was involved in the case. “I once asked him how a jury could deadlock at 6-6 over something like this,” he said. “After all, a minister was shot in a church, and it was seen by 300 people, all of whom stampeded over each other trying to get out of the building.”

Denson told him it came down to Southern folk justice. If anyone deserved to be shot it was him, folk justice holds.

There’s some irony here. Lee’s enduring novel ends with such a killing. When Atticus Finch is told by Sheriff Heck Tate that Bob Ewell has been found dead with a butcher knife lodged in his chest, Finch first thinks his son Jem might have done it to protect his sister Scout. The sheriff told him Jem couldn’t have done it because his shoulder had been separated in a struggle with Ewell, leaving only reclusive neighbor Boo Radley as the prime suspect. The sheriff said enough killing had taken place and he would not put a mentally challenged young man in the public limelight of a trial. “Bob Ewell fell on his knife,” Sheriff Tate said. “I may not be much, but I am still the sheriff of Macomb County, and Bob Ewell fell on his knife.”